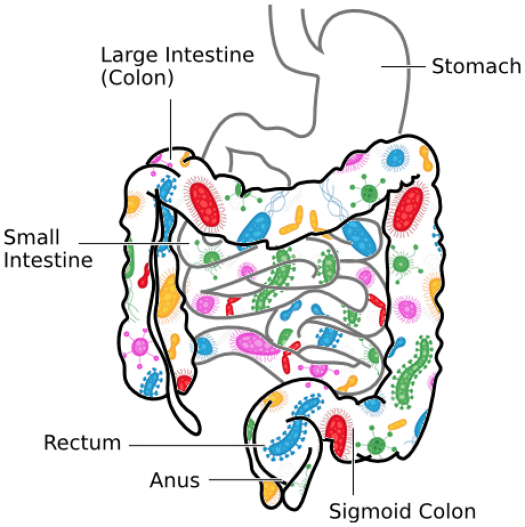

colon-intestines-bacteria.png

Collage by FAIM / Source file from wpclipart.com

Introducing healthy gut bacteria can solve a number of issues.

In 2011, Michael Hurst was scheduled for surgery to remove a portion of his colon. Diagnosed at age 21 with ulcerative colitis, he had suffered with bloody diarrhea, gas, and severe abdominal pain for more than 12 years. Despite treatment with intense regimens of antibiotics, prednisone, and other medications, his flare-ups worsened, and his doctors told him surgery was his only option.

Three days before he was scheduled to check into the hospital, Michael learned about fecal transplant as a treatment for ulcerative colitis. As he discusses in his book (entitled, believe it or not, Poop Power), he canceled his surgery, made a diluted infusion of stool donated by a healthy friend, and used an enema to self-administer this therapy. Michael’s “incurable” condition has been in remission for three years now.

“Icky” but highly therapeutic

Fecal transplant is an incredibly powerful therapy. The first recorded treatment was in 1958, when a patient with a life-threatening intestinal infection had an immediate and dramatic response. Nevertheless, for 50 years this highly effective therapy was ignored in favor of antibiotics. Now, thanks to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria, antibiotics are losing their luster, and – despite the “ick factor” – fecal transplant is coming into its own.

The first significant clinical trial of this therapy was published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine. Patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infections – which cause severe and painful diarrhea in millions of Americans and kill 14,000 every year – were treated with either the usual antibiotics or “infusions of donor feces.” After just one fecal transplant, 81 percent had rapid and complete resolution, and two-thirds of the non-responders were cured after a second infusion from a different donor. It was so much more effective than antibiotics, which had a 27 percent response rate, that the study was stopped early so all participants could receive fecal transplants.

Thousands of additional patients have reported treatment success not only for ulcerative colitis and C. difficile infections but also Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and other difficult conditions. Australian researchers, for example, reported that 70 percent of patients with chronic fatigue had a positive response.

Butt out, FDA!

Demand for fecal transplants has skyrocketed since the 2013 clinical trial demonstrating its clear superiority over antibiotics for potentially fatal intestinal infections. More and more conventional physicians were offering this life-saving therapy – until the FDA butted in with onerous restrictions on its use.

Updated regulations now allow treatment for patients with C. difficile infections who are unresponsive to antibiotics, as long as the donor is known to the physician or patient and has been tested appropriately. For all other conditions, doctors must file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application – an unnecessary, burdensome requirement that is stifling research and denying patients access to an effective non-drug treatment.

The agency is getting serious pushback. Gastroenterologists have proposed treating fecal transplants like blood transfusions, with careful screening of donors and stool for communicable diseases. And many desperate patients who are unable to obtain treatment are going the do-it-yourself route. The FDA needs to stop protecting their buddies in Big Pharma and just get out of the way.

Other products go by pycnogenol (with a little p), and grape seed extracts are frequently referred to as proanthocyanidins or OPCs. What you really need to know is that high-quality supplements from reputable manufacturers – from pine bark and grape seeds – have more similarities than differences.

Restores healthy gut bacteria

The power of this low-tech treatment, which simply introduces healthy bacteria into the intestinal tract, underscores the critical role of the human microbiota – the 100 trillion microbes that live in and on our bodies and are concentrated in the gut.

Each of us has a unique microbial “community” that varies from one person to another based on diet, environment, genetics, age, and medical history. These variations influence our intestinal health, resistance to infection and disease, metabolism, mood, and even our weight. For example, the microorganisms in the guts of lean people are quite different from those who are obese. And older people tend to have less diverse intestinal flora, which may be associated with some age-related health challenges.

Modern life is not kind to our microbiota. American doctors prescribe nearly 260 million courses of antibiotics every year, often for conditions they have zero chance of benefitting. Antibiotics kill good bacteria along with the bad, destroying the normal microbial balance and allowing pathogenic species to gain a foothold. Other factors that upset this balance include our highly processed, nutrient-deficient diet, laden with chemicals and antibiotic residues, and our obsession with cleanliness (e.g., the popularity of antibacterial soaps). Almost all C. difficile infections are attributed to antibiotic use, and our dramatically increased incidence of allergies, asthma, eczema, digestive disorders, obesity, and autism are due at least in part to disruptions in the gut microbiota.

Eat right...

You can protect yourself by eating more fermented foods, which contain a rich variety of beneficial bacteria to repopulate the gut. Yogurt, kefir, and other “sour” milk products have been recognized for their health properties since Biblical times. Sauerkraut and pickled vegetables also pack a therapeutic punch, as do kimchi, a spicy pickled cabbage Korean favorite, and miso and tempeh, which hail from Japan.

Make prebiotics part of your regular diet, too. Prebiotics are indigestible carbohydrates that pass through the digestive system more or less intact – until they hit the large intestine, where they feed and nourish the resident bacteria. Soluble fiber in beans, legumes, oats, barley, flax, and other whole grains as well as onions, garlic, asparagus, carrots, broccoli, kiwi, bananas, citrus, and berries all have excellent prebiotic properties.

...And take probiotics

I also recommend probiotic supplements. You probably know that probiotics help with the usual digestive problems such as gas, bloating, and constipation and are used to treat acute and antibiotic-related diarrhea and irritable and inflammatory bowel conditions. But dozens of additional benefits have been reported in recent years for conditions as diverse as vaginal infections and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to respiratory infections and weight loss. Probiotic supplements have even been shown to lower levels of stress hormones and improve symptoms of depression, anxiety, and anger.

Research on the human microbiome and the power of probiotics is rapidly expanding, and I’ll keep you posted as important findings emerge. But for now, I’ll tell you what I’ve been telling my patients for 35 years: Take a few billion bacteria and call me in the morning!

My recommendations

- Make fermented and high-fiber foods, which are rich in pre- and probiotics, part of your regular diet.

- Consider adding probiotics to your daily supplement regimen. If you’re on an antibiotic, probiotics are a must – just make sure you take the supplement three hours before or after taking the drug. Look for a product from a reputable manufacturer that contains both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains, and take as directed.

- For serious intestinal issues, look into fecal transplant. To learn more, visit thepowerofpoop.com and fecaltransplant.org, where you’ll find a number of success stories, clinics offering the therapy, and – not for the faint of heart – do-it-yourself instructions.

To learn more, visit Dr. Whitaker's website.

References

Borody TJ, et al. The GI microbiome and its role in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A summary of bacteriotherapy. Journal of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine. 2012 Dec;31(3):3–8.

Kelly CP. Fecal microbiota transplantation – an old therapy comes of age. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368:474–5.

Petschow B, et al. Probiotics, prebiotics, and the host microbiome: the science of translation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013 Dec;1306:1–17.

van Nood E, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368(5):407–15.

Originally published in Health & Healing, Vol. 24, No. 7, July 2014. Used with permission.