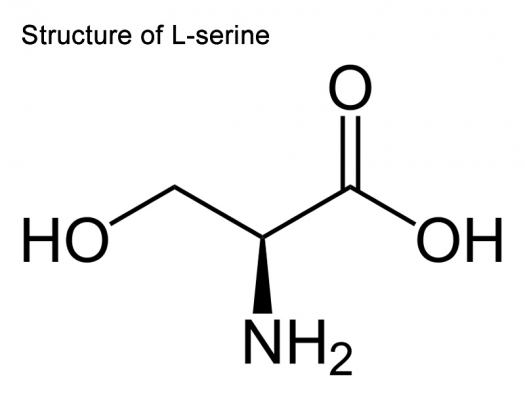

L-Serine-structure.jpg

Image by NEUROtiker / Wikimedia Commons

Guam is a US territory in the Mariana Islands in the Western Pacific. Between 1940 and 1965, the island’s original inhabitants, the Chamorro, were decimated by what they call lytico-bodig, a devastating disease with features of ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Lou Gehrig’s disease), Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s. At its peak in the 1950s, the Chamorro’s incidence of ALS was 50-100 times greater than anywhere else, but after the mid-60s it dropped off, and disease rates today are on par with the rest of the world.

Researchers have studied this mysterious illness for decades, looking at genetics, nutritional deficiencies, infectious agents, and the like, but nobody could figure it out until Paul Alan Cox, PhD, got involved. And what he discovered is key to a potential breakthrough in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, and other neurodegenerative diseases.

A medical whodunit

At age 19, Dr. Cox spent two years as a Mormon missionary on the Pacific island of Samoa. After earning a PhD and working in a number of prestigious positions, he returned to Samoa with his family to study traditional medicine with local healers. While he was there, he helped protect 30,000 acres of rainforest that are home to hundreds of species – including the flying fox, a huge fruit-eating bat with a wingspan of up to four feet.

When Dr. Cox heard about lytico-bodig, he flashed on these bats, which he had studied for his doctoral dissertation at Harvard. Flying foxes also live on Guam and other Pacific islands and are a favorite food of some native populations. The bats feed on the seeds of cycad trees, which contain a powerful neurotoxin: the amino acid beta-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA).

It took some scientific sleuthing, but Dr. Cox and his team figured out that BMAA is produced by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) that live in shallow pools of water and are taken up by the trees’ roots and into their seeds. When flying foxes eat cycad seeds, BMAA builds up to toxic levels in their fat and ends up in the bat stew that the Chamorro consider a prized delicacy. Why the 25-year uptick and subsequent drop-off? The guns and money brought to Guam after World War II resulted in easier hunting, increased consumption – and eventually to the extinction of flying foxes in Guam.

A culprit is identified...

Since Dr. Cox published his initial findings in 2002, studies have confirmed that lab animals fed BMAA develop neurodegenerative symptoms similar to those of lytico-bodig. Exposed animals also develop amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain and behavior changes characteristic of Alzheimer’s later in life. High concentrations of BMAA have been detected in the brains of Chamorro people who died of this disease – as well as in some North Americans who died of Alzheimer’s. Clusters of ALS have been observed near bodies of water with frequent cyanobacteria/blue-green algae blooms, and the likely culprit is BMAA.

With prolonged or excessive exposure, BMAA insinuates itself into proteins in the brain, causing them to “misfold” and develop structural abnormalities that lead to neuronal dysfunction and death. Protein misfolding and tangling, such as tau and amyloid in Alzheimer’s and SOD1 in ALS, is an underlying culprit in most neurodegenerative diseases.

To pursue this line of research, Dr. Cox put together the Brain Chemistry Labs, a consortium of 50 international scientists, to find a solution for these diseases. Their most exciting discovery to date is that a specific amino acid reduces BMAA toxicity, prevents protein misfolding, and protects against neurodegeneration.

...And a new therapy is proposed

L-serine is a safe, inexpensive amino acid that is sometimes recommended by alternative doctors for chronic fatigue. As it turns out, it is also key to how BMAA does its damage. This toxin homes in on proteins and displaces L-serine in amino acid chains, resulting in the misfolded, tangled proteins implicated in Alzheimer’s, ALS, and other brain diseases. Adding L-serine to human cell cultures blocks the insertion of BMAA, stops protein misfolding, and thus prevents neuronal damage.

Animal studies show that adding L-serine to the diet reduces the risk of neurodegenerative disease. In a 2016 study, researchers fed bananas laced with BMAA, L-serine, or a combo of the two to monkeys that are genetically at risk of developing dementia. The brains of the animals who had eaten BMAA alone were riddled with Alzheimer’s-like amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles. Those who had been given BMAA plus L-serine, however, had 80-90 percent fewer disease markers.

Population studies also point to L-serine’s neuroprotective effects. Ogimi is a small village on one of Japan’s southern islands that boasts the world’s highest number of centenarians per capita plus remarkably low rates of dementia. Researchers attribute this to the residents’ close community ties, active lifestyle, and healthy diet, which includes a lot of L-serine-rich tofu, seaweed, pork, and soybeans. Older Ogimi women, for example, eat more than 8 g of L-serine per day, compared to American women’s 2.5 g.

Human clinical trials are underway. Phase I studies involving patients with ALS proved that supplemental L-serine in doses up to 15 g twice a day is safe – and the highest dosage slowed disease progression by an astounding 85 percent! Phase II studies are now testing the effectiveness of 30 g of L-serine per day on patients with Alzheimer’s or ALS.

L-Serine: safe, inexpensive, and available

More than 5.8 million Americans have Alzheimer’s, and that number is expected to soar to 14 million by 2050. The need to come up with therapies for Alzheimer’s is more urgent than ever. Will that therapy be L-serine? Maybe, maybe not. Nevertheless, this research is among the most innovative and exciting in years.

From a strictly research perspective, it’s premature to take supplemental L-serine as a preventive. However, it’s clear that chronic exposure to BMAA causes degenerative changes in the brain. It’s also clear that this neurotoxin isn’t found only in cycad fruit-eating bats in Guam. The EPA reports that toxic blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) blooms are a major environmental problem in all 50 states. And early research suggests L-serine may have broader neuroprotective effects, acting as a warning system that alerts brain proteins against misfolding.

L-serine is safe, cheap – and I’m taking it.

References

Bradley WG, et al. Studies of environmental risk factors in ALS and a phase I clinical trial of L-serine. Neurotox Res. 2018 Jan;33(1):192–8.

Cox PA, et al. Dietary exposure to an environmental toxin triggers neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain. Proc Biol Sci. 2016 Jan 27;283(1823). pii: 20152397. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2397.

Cox PA, et al. Traditional food items in Ogimi, Okinawa: l-serine content and the potential for neuroprotection. Curr Nutr Rep. 2017;6(1):24–31.

Originally published in Dr. Whitaker's Health & Healing newsletter, July 2019. Used with permission.