hipjoint-normal-osteoporosis.jpg

Illustration by Andrea Danti, Copyright / 123rf.com

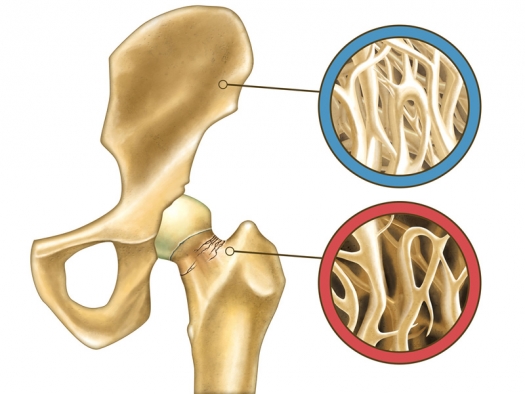

Skeleton close-up showing normal bone and osteoporosis. Digital illustration.

Has your doctor given you the grim news: "You have osteopenia and you're heading toward full-blown osteoporosis"? Is your doctor pressuring you to take Fosamax? If you've been reading my articles for very long, you know how dangerous Fosamax and other bisphosphonates can be. But osteopenia is a serious condition, isn't it?

No, it's not. In fact, it's not serious and it's not even a disease.

Let me tell you how I discovered the truth about osteopenia. Hopefully, it will prevent you from unnecessarily taking dangerous drugs.

When I was in my early 40s, I had the opportunity to participate in an osteoporosis study at UCLA (the University of California, Los Angeles). After filling out several pages of my health history, I went into a room housing a machine that measured the bone density in my heels. Two weeks later, the doctor in charge of this study called me. He was puzzled. The density in my left heel was fine, but my right heel showed signs of deterioration. Could I come in for a re-test, he asked?

Of course, I could. And the results of this second bone scan were even more puzzling. This time my right heel was fine and my left heel was thinner.

I spoke with the doctor and asked him how measuring my heels could be an indication of my risk for future fractures in other areas – like my hip or spine. He didn't know. Nor could he explain my results. So I dropped out of the study. I realized that even carefully conducted university studies using impressive machines could have serious limitations. I never considered the possibility that the drug and medical communities would ever manufacture a disease just to sell expensive tests and prescription drugs.

Call me naive.

Now I know better. So if your doctor says you have osteopenia and he gives you a medication like a bisphosphonate (Fosamax) for it, here are some things you need to consider before you agree to take it:

Osteopenia is not a disease. Osteopenia is the normal slight thinning of bones that comes with aging. While many doctors think it's a precursor to osteoporosis, not everyone with osteopenia gets osteoporosis. "It was just meant to show a huge group who looked like they might be at risk," says an osteoporosis epidemiologist who helped define osteopenia back in 1992. It was never meant to identify a disease. What changed this? A drug company called Merck.

Merck released Fosamax in 1995. It was the first non-hormone drug said to stop osteoporosis. Fosamax was Merck's golden goose. The problem was, women weren't buying it. So Merck found some marketers to change this.

Their solution was to get more women diagnosed with osteoporosis by having bone scans. But scans were expensive and there were few testing centers. So Merck created a nonprofit organization called the Bone Measurement Institute with one sole employee: The marketer they hired to increase Fosamax sales.

He did this by funding the development of less expensive portable machines rather than the large, expensive ones. The less expensive machines brought down the price of bone scans. One problem was that these portable machines measured bone density at the heel, wrist, forearm, or finger. Not at the hip or spine, where fractures are more likely to lead to death.

Meanwhile, Merck funded studies, leased bone scan machines to doctors, and convinced Medicare to reimburse for measuring scans. Sales rose, but apparently not enough for Merck. So they developed a low-dose Fosamax for women with osteopenia. And when women saw the word "osteopenia" on their bone scan reports, they believed they needed treatment. So did many of their clinicians.

Osteopenia doesn't increase your risk for broken bones. According to Dr. Susan Ott, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Fosamax may increase your bone density, but it doesn't decrease the number of fractures. I've been saying this for years.

But that's not all.

We have no long-term studies to tell us what happens to women who start taking Fosamax in their 50s and 60s for osteopenia. Do they prevent fractures later on? No one knows, and I couldn't find any studies planned to find out.

Bisphosphonates, such as Fosamax are more harmful than helpful. In some cases, bisphosphonates cause the jaw and other bones to become brittle and die. Over the past few years, I've seen more evidence that while Fosamax may increase bone density, it is more destructive than beneficial. You can – and should – read more about this in past articles on my database.

What you can do... safely

If your doctor says you have osteopenia, the first thing you can do is to stop worrying. It is just a sign of a potential problem. Get a vitamin D blood test to make sure your vitamin levels are between 50 and 80. Vitamin D will help protect your bones better and more safely than Fosamax.

Eat a balanced diet, including whole grains, nuts, seeds, and green leafy vegetables high in both calcium and magnesium. Take no more than 500 mg of each in your supplements. Get the rest from your diet. Dietary calcium is much better absorbed than supplements. Don't overdo supplemental calcium. It won't save your bones and it could make them brittle. Instead, increase your magnesium to bowel tolerance (enough for comfortably soft stools). Magnesium makes bones more flexible.

Get regular bone-stressing exercise.

Remember, there's a difference between a potential indicator of a disease and a full-blown disease process. Just because you have osteopenia doesn't mean you're destined to get osteoporosis. In fact, you can make sure you don't suffer from the bone disease. Take these precautions, but don't get over treated.

For more information, I urge you to read or listen to this expose on osteopenia at NPR: "How A Bone Disease Grew To Fit The Prescription," by Alix Spiegel, NPR, December 21, 2009.